I hear this comment and/or question often when talking to Connecticut libraries, historical societies, senior centers and community centers. They’re trying to figure out how to expend limited resources based on what questions have come to them. Unfortunately, the starting point is probably flawed.

As a professional genealogist, I actually use my library’s resources (specifically their FamilySearch affiliate status) regularly. However, FamilySearch doesn’t keep access statistics. Since I use their WiFi connection and don’t ask the reference staff questions, there’s no way for the library to tell that the resource is being used.

In speaking to researchers, most research questions are not making it to the local library’s reference desk. The more tech savvy are starting with Google or the FamilySearch Wiki. The less tech savvy are contacting the local historical society where their ancestors lived, much to the chagrin of those of us who are more advanced. (Please don’t default to using Ancestry when everyone contacts you!) Yet, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a need.

How do you find out what’s needed? Ask! Ask your patrons. Or ask local professional genealogists in your area. People do call us with questions.

Here’s what I explain the most often (in response to questions):

- How to access resources at the State Library

- How to use FamilySearch

- How to find a FamilySearch affiliate. (If your organization isn’t one, and you have public computers, it’s a great option!)

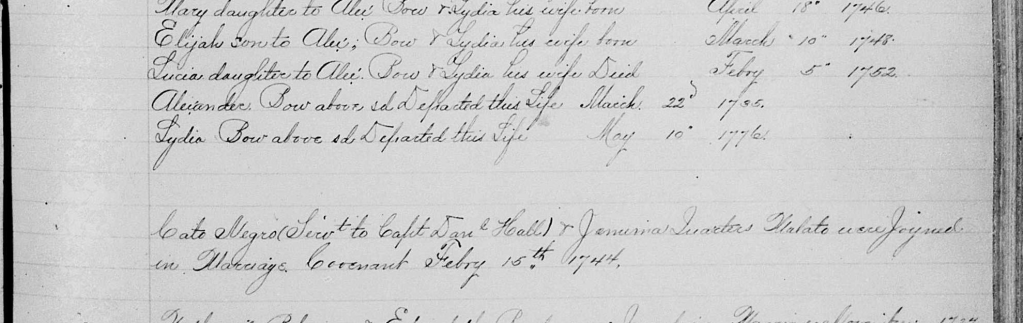

- What Connecticut records are stored where

- Questions about ethnic and regional resources

- How to find a professional genealogist

If you aren’t sure if your organization can support a program, consider bringing several organizations together to host.