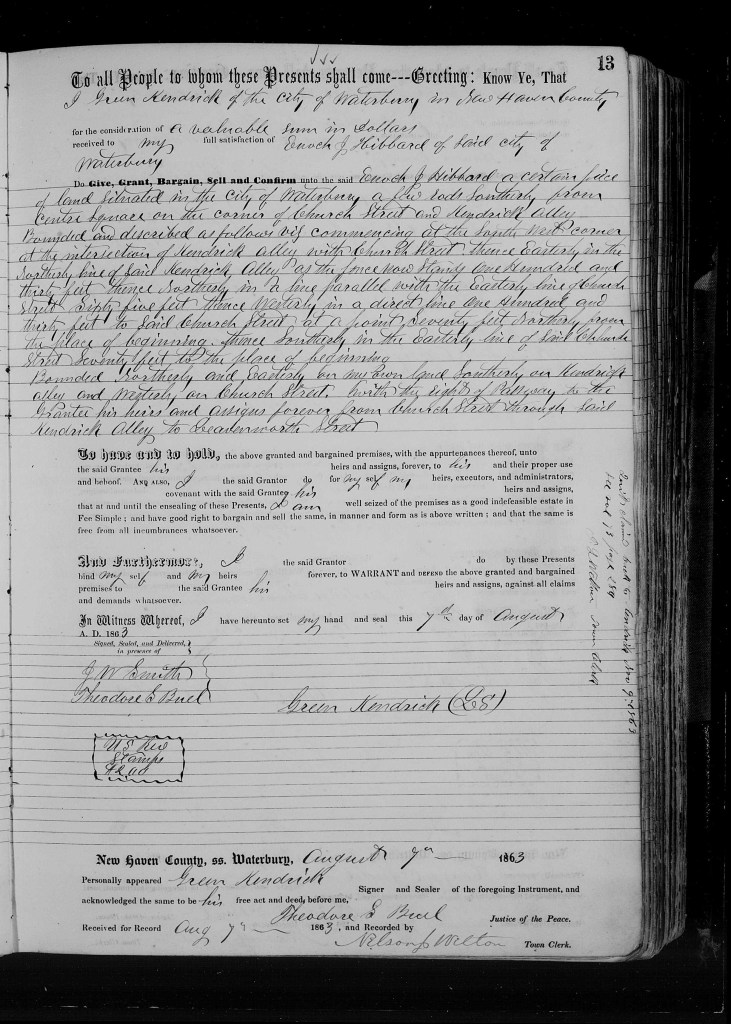

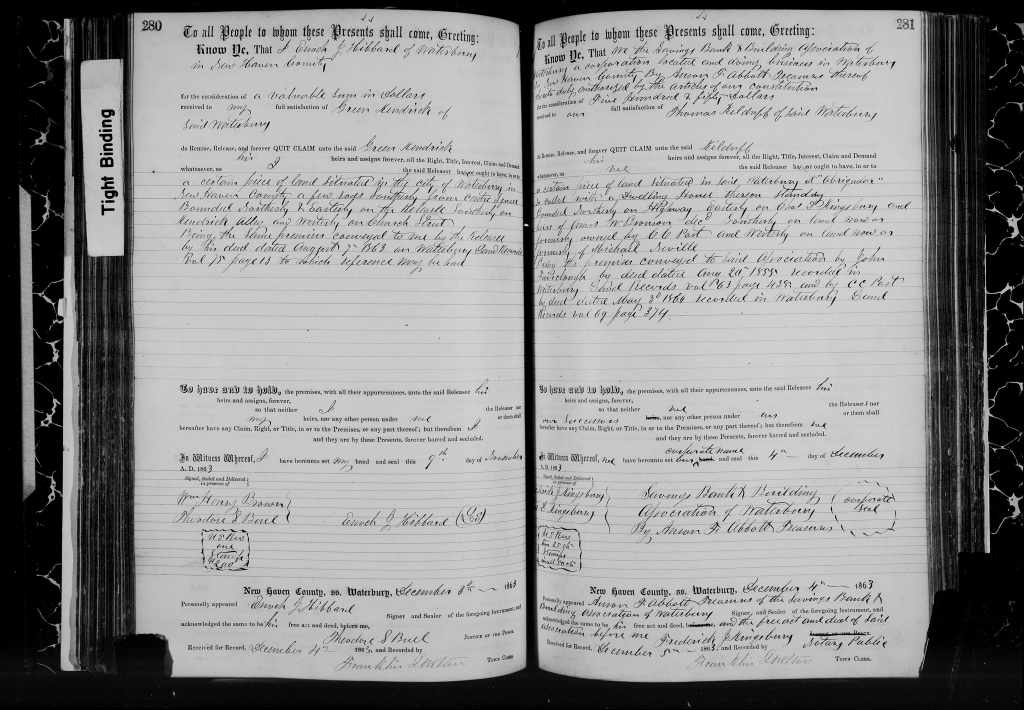

And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That the several towns within this State shall forthwith choose a committee who shall divide all the inhabitants thereof, who give in a list or are included in any militia roll, either of the trainband, alarm list or companies of horse, into as many classes according to their list as such town shall be deficient in number of men,and each of said classes shall on or before the first day of February next procure a good able-bodied effective recruit to serve during the war or for three years[…]

Military Obligation: The American Tradition, Special Monograph No. 1, Volume II, Part 2, Connecticut Enactments (N.P.: The Selective Service System, 1948), 174-175; digital images, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/Military_Obligation_Connecticut_Enactmen/YpxHAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22An%20act%20for%20filling%20up%20this%20state’s%20quota%20of%20the%20Continental%20Army.%22&pg=PA238&printsec=frontcover)

By 1780, the Continental Army was short handed. A request was sent to the states to supply a certain number of men. In response, Connecticut instituted what might be described as an early version of the draft. Each town was assigned a certain number of men to provide. The 1780 quota act offered a method for filling the positions.

The act’s impact was especially significant for Connecticut’s men of color. The act permitted the engagement of substitutes in order to meet the quota. Individuals held in slavery were not subject to the state’s militia laws, and therefore, were not already required to serve. Connecticut’s units were integrated, so men of color could serve. “Hiring” an enslaved individual to serve as a substitute became a common practice.

If your ancestor enlisted in the Continental Army about 1780, the quota system was likely the reason why.