Since the 2006 release of Denis Caron’s A Century in Captivity: The Life and Trials of Prince Mortimer, a Connecticut Slave, discussion of the life of Prince Mortimer of Middletown has largely centered around the trial for attempted murder that resulted in Mortimer’s imprisonment in Old New-Gate Prison.[1] Yet some studies of Mortimer have referenced Revolutionary Service for Mortimer. One author indicated: “During the American Revolution Prince served various officers and was sent on errands by George Washington.”[2] As new scholarship increases the understanding of the role of veterans of color in the American Revolution, it is worth asking: how accurate were such claims?

The Source

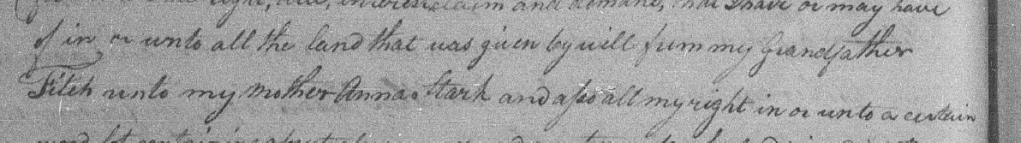

Claims about Prince Mortimer’s Revolutionary War service appear to date to 1860. In that year, Richard Harvey Phelps published A History of Newgate of Connecticut, at Simsbury, Now East Granby. In a discussion of Prince Mortimer, Phelps explains that “He [Mortimer] was a servant to different officers in the Revolutionary war; had been sent on errands by General Washington, and said he had ‘straddled many a cannon when fired by the Americans at British troops.”’[3] Although Phelps claims to quote Mortimer, he cites no source for a statement printed over twenty years after Mortimer’s death.

A Servant?

Body servants – individuals assigned as servants to certain officers – have been documented in Connecticut units during the American Revolution.[4] The best known of these men is likely Jordan Freeman, body servant to Col. William Ledyard, who was killed during the Battle of Groton Heights.[5] Other documented body servants include Jethro Martin, servant to Col. David Humphreys and “Kitt” Putnam, servant to Gen. Israel Putnam.[6] Accounts of Kitt Putnam’s age suggest he may have begun service after the War, but his role hints that Putnam may have had a prior servant.[7]

Except for Martin, whose legal status and history is unknown, each of these men appears to have had a personal connection to the officer whom they served.[8] Freeman, although free at the time of the War, was formerly enslaved by the Ledyard family.[9] Putnam remained with General Putnam’s son after the elder Putnam’s death, suggesting either enslavement or a strong tie.[10] Although the limited number of cases currently documented impacts any survey, the available evidence suggests that most body servant served a single officer. The claims about Mortimer serving multiple officers would therefore be outside the norm.

Another Role?

Soldiers of color had a well-documented place in Connecticut’s Revolutionary War Army. As one author claimed, “[…] by 1777, almost every unit in Connecticut had a black soldier.”[11] Is it possible that Mortimer’s claims of service came not from a role as a body servant but as a soldier ?

Mortimer’s purported age would suggest against another role. Phelps put Mortimer’s birth year as about 1724.[12] That would have made him 52 at the start of the Revolutionary War. Mandatory military service ended at 45, and although men up to 60 could be called up for alarms, their service was not as intense.[13] It was possible for an older man to volunteer and still serve.[14]

Yet, Mortimer’s legal status would have limited his ability to volunteer himself. Prince Mortimer was enslaved to Philip Mortimer, the owner of Middletown’s ropewalk.[15] Rope spinners, Prince Mortimer’s documented trade, were considered skilled workers and would have been essential for the ropewalk to complete its product.[16] The decision of Prince Mortimer’s service would have been made by his enslaver.

Such service seems likely only if the 1780 quota act came into play. The act required each town to provide a certain number of recruits for the Continental Army.[17] The enlistment of enslaved men provided a way for the towns to meet that quota.[18] Middletown’s quota records are not publicly accessible, and it is possible Prince Mortimer was engaged under the act to protect another family member from serving.

Is it possible that the account is wrong?

It is very possible that the account is inaccurate. First, A History of Newgate was not published until 1860, decades after the start of the Revolution and over twenty years since the death of Prince Mortimer. Such a gap in time would allow for memories of events to weaken. Second, the information is unsourced. Third, and most importantly, the phrasing in the narrative resembles that of the “Loyal Slave” narrative that began to be widely recounted in the years after the Civil War.[19] For a discussion of the subject, visit https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/features/essays/ray_wise/. While Mortimer’s apparent loyalties are to the leaders of the Revolution, the wording is too close to be ignored. What was Phelps trying to convey by the choice?

What research is still needed?

Two pieces of information would be helpful to clarify Prince Mortimer’s actual role during the American Revolution. The first would be his actual age or a close approximation thereof. While accounts put him at 110 at death, the available statistics suggest that reaching such an age would be rare even thirty years later.[20] That estimate of 110 would also suggest, based on Philip Mortimer’s will, that the Mortimer family expected Prince Mortimer to labor on the ropewalk into his early 70s before he could be manumitted.[21] Such a condition would be illegal under a May 1792 Connecticut law, which permitted the emancipation of an enslaved individual only if they were under 45.[22] Philip Mortimer’s will is dated July 1792.[23] A more accurate estimate of Prince Mortimer’s age would allow for a better accounting of his possible roles in the Revolution. The second is a better understanding of the economic dynamics of the ropewalk, especially in comparison to the pay for a body servant or soldier. Would it have made sense, either economically or socially, for Philip Mortimer to have sent Prince Mortimer to War?

[1] Josh Kovner, “Writer Tells Story of Old Slave; Man Died at 110 in State Prison,” Hartford Courant, 3 May 2006, page B5; digital images, ProQuest (https://www.proquest.com/hartfordcourant/newspapers/writer-tells-story-old-slave-man-died-at-110/docview/256989475/sem-2?accountid=46995: accessed 6 February 2025).

[2] Karl J. Winter, “Prince Mortimer (CA. 1724-1834),” BlackPast, 8 March 2007 (https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/mortimer-prince-ca-1724-1834/: accessed 6 February 2025).

[3] Richard Harvey Phelps, A History of Newgate of Connecticut (Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1860), 101; digital images, Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/historyofnewgate00phel/page/100/mode/2up: accessed 6 February 2025).

[4] “Body Servant,” Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/body%20servant: accessed 6 February 2025).

[5] “Jordan Freeman” CT State Library (https://libguides.ctstatelibrary.org/c.php?g=1416831: accessed 6 February 2025). “History,” Jordan Freeman Chapter DAR (http://jordanfreemandar.org/history.htm?fbclid=IwY2xjawIRgmlleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHdBd2Bhpq6fiZW6s2JuFEV2ABfUushnWAkr9GfOTYDbpIGgzaTjcsjCkSA_aem_efdhjdHjcVzHXJOzqNb-zw: accessed 6 February 2025).

[6] “David Humphreys (1752-1818)”, George Washington’s Mount Vernon (https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/david-humphreys-1752-1818: accessed 6 February 2025). S.P. Hildreth, Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co, 1848), 388; digital images, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pioneer_History/dyoVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22kitt%20putnam%22&pg=PA388&printsec=frontcover: accessed 6 February 2025).

[7] Hildreth, Pioneer History, 388

[8] “David Humphreys (1752-1818).”

[9] “History.”

[10] Hildreth, Pioneer History, 388.

[11] “The True Story of Chatham Freeman,” The 6th Connecticut Regiment (https://www.6thconnecticut.org/page4: accessed 6 February 2025).

[12] Phelps, A History of Newgate of Connecticut, 101.

[13] John K. Robertson, “Decoding Connecticut Militia 1739-1783,” Journal of the American Revolution (https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/07/connecticut-militia-1739-1783/: accessed 6 February 20250.

[14] Robertson, “Decoding Connecticut Militia 1739-1783,” Journal of the American Revolution.

[15] “Ropewalks of Essex,” Town of Essex, Connecticut (https://www.essexct.gov/home/pages/ropewalks-of-essex: accessed 6 February 2025).

[16] Middletown CT, Probate Records, Vol. 6, page 191, will of Philip Mortimer; digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L92K-B278?view=fullText&keywords=Philip%20Mortimer&lang=en&groupId=TH-1971-45598-17969-60 : accessed 6 February 2025). “11. Life as a Ropemaker,” B. Keith Ropemaker (https://bkeithropemaker.com/Rope_Chapt_11.html: accessed 6 February 2025). “Ropewalks of Essex,” Town of Essex, Connecticut.

[17] Bryna O’Sullivan, “What was the 1780 quota act – and why does it matter?” Connecticut Roots (https://connecticutroots.org/2024/11/24/what-was-the-1780-quota-act-and-why-does-it-matter/: accessed 6 February 2025).

[18] O’Sullivan, “What was the 1780 quota act – and why does it matter?” Connecticut Roots.

[19] Kevin M. Levin, “The Pernicious Myth of the ‘Loyal Slave’ Lives on in Confederate Memorials,” Smithsonian Magazine, 17 August 2017 (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pernicious-myth-loyal-slave-lives-confederate-memorials-180964546/: accessed 6 February 2025).

[20] “Health History: Health and Longevity Since the Mid-19th Century,” Stamford Medicine: Ethnogeriatrics (https://geriatrics.stanford.edu/ethnomed/african_american/fund/health_history/longevity.html: accessed 6 February 2025)

[21] Middletown CT, Probate Records, Vol. 6, page 191, will of Philip Mortimer.

[22] Acts and Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson & Goodwin, 1805), 399; digital images, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433009068960?urlappend=%3Bseq=421%3Bownerid=27021597768686807-465: accessed 6 February 2025).

[23] Middletown CT, Probate Records, Vol. 6, page 191, will of Philip Mortimer.